| Table of Contents

| Function Reference

| Function Finder

| R Project |

HIERARCHICAL REGRESSION

Preliminaries

I am not well read on the topic of hierarchical regression, so for details,

especially on theory, you'd be well advised to consult another source. I've

found a textbook by Keith (2006) to be very helpful. It is well written and

gets to the point without getting bogged down in a lot of mathematical finery.

What theory I do present here is adapted from that source. I'm also going to

borrow a data set from him. Kieth, by the way, refers to hierarchical

regression as sequential regression. Other resources I found helpful were

Petrocelli (2003), who discussed common problems with and misuses of

hierarchical regression, and Lewis (2007), who compared hierarchical with

stepwise regression.

I felt it necessary to create this tutorial to support another

on Unbalanced Factorial Designs. As we'll find

out, Type I sums of squares, the R default in ANOVA, does something similar

to hierarchical regression, but not quite exactly. There is a difference in

the error terms that are used, which I'll discuss below.

- Lewis, M. (2007). Stepwise versus hierarchical regression: Pros and cons.

Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Southwest Educational Research

Association, February 7, 2007, San Antonio. (Available online here.)

- Keith, T. Z. (2006). Multiple Regression and Beyond (1st ed.).

Boston: Pearson/Allyn and Bacon. (I understand there is now a second

edition available.)

- Petrocelli, J. V. (2003). Hierarchical multiple regression in counseling

research: Common problems and possible remedies. Measurement and

Evaluation in Counseling and Development, 36, 9-22.

Some Data

Timothy Keith, in his textbook Multiple Regression and Beyond,

uses a data set that is well suited to

demonstrating hierarchical regression and how it is different from standard

Multiple Regression. These data are available

at Dr. Keith's

website.

Click the link above, then scroll down until you come to a boldfaced

section called "Shorter version of the NELS data (updated 5/9/15)."

At the end of this paragraph is a link that begins "n=1000...". Click it

and download the zip file it links to. Drag that file to someplace where it

is convenient to work with it (I use my Desktop), then unzip it. That will

create a folder with the ungainly name "n=1000stud-par-shorter-5-19-15-update".

Open this folder and find a file with the equally ungainly name

"n=1000, stud & par shorter all miss blank.csv". Change the name of that file

to Keith.csv and drag it to your working directory (Rspace). You can throw the

rest of the folder away now. (Not that there isn't anything interesting in it,

but nothing we'll be using.) The file is a CSV file with missing values left as

blanks. Fortunately, R should be able to deal with this in a CSV file by

automatically converting the blank data values to NA. Load the data as follows.

> NELS = read.csv("Keith.csv")

> summary(NELS) # output not shown

I'm not going to show the summary output because there is a LOT of it! We want

to work with only five of those many, many variables, so the easiest thing to

do would be to extract them into a more manageable data frame. That's going to

require some very careful typing, or some moderately careful copying and

pasting.

> grades1 = NELS[,c("f1txhstd","byses","bygrads","f1cncpt2","f1locus2")]

> dim(grades1)

[1] 1000 5

> summary(grades1)

f1txhstd byses bygrads f1cncpt2

Min. :28.94 Min. :-2.41400 Min. :0.50 Min. :-2.30000

1st Qu.:43.85 1st Qu.:-0.56300 1st Qu.:2.50 1st Qu.:-0.45000

Median :51.03 Median :-0.08650 Median :3.00 Median :-0.06000

Mean :50.92 Mean :-0.03121 Mean :2.97 Mean : 0.03973

3rd Qu.:59.04 3rd Qu.: 0.53300 3rd Qu.:3.50 3rd Qu.: 0.52000

Max. :69.16 Max. : 1.87400 Max. :4.00 Max. : 1.35000

NA's :77 NA's :17 NA's :59

f1locus2

Min. :-2.16000

1st Qu.:-0.36250

Median : 0.07000

Mean : 0.04703

3rd Qu.: 0.48000

Max. : 1.43000

NA's :60

If you're getting that summary table, then you're ready to go.

> rm(NELS) # if you don't want it cluttering up your workspace

Some Preliminary Data Analysis

NELS stands for National Educational Longitudinal Study. NELS was a study

begun in 1988, when a large, nationally representative

sample of 8th graders was tested, and then retested again in 10th and

12th grades. These aren't the complete NELS data but 1000 cases chosen,

I assume, at random.

We will attempt to duplicate the analysis in Keith's textbook (2006), which

appears to have been done with SPSS. Let's begin by duplicating the descriptive

statistics (Figure 5.1, page 75). The minimum and maximum we already have. We

also already have the means, but we'll get them again, as it only takes two

seconds. Okay, maybe three. Because our data frame is all numeric, we can use

a shortcut instead of doing this variable by variable.

> apply(grades1, 2, mean, na.rm=T) # margin 2 is the column margin

f1txhstd byses bygrads f1cncpt2 f1locus2

50.91808234 -0.03120500 2.97039674 0.03973433 0.04703191

> apply(grades1, 2, sd, na.rm=T)

f1txhstd byses bygrads f1cncpt2 f1locus2

9.9415281 0.7787984 0.7522191 0.6728771 0.6235697

> sampsize = function(x) sum(!is.na(x))

> apply(grades1, 2, sampsize)

f1txhstd byses bygrads f1cncpt2 f1locus2

923 1000 983 941 940

Because of the missing values, we couldn't use length()

to get the sample sizes. We had to write a short function that counts up the

number of values that are not missing.

Now we'll try to duplicate Table 5.1 on page 76, which is a correlation

matrix. Given that we have multiple missing values in the data, we're

going to have to figure out how to choose cases to use in calculating

the correlations. My first inclination is to use all pairwise complete cases.

> cor(grades1, use="pairwise.complete")

f1txhstd byses bygrads f1cncpt2 f1locus2

f1txhstd 1.0000000 0.4387503 0.4948496 0.1791069 0.2474076

byses 0.4387503 1.0000000 0.3352870 0.1383291 0.2032299

bygrads 0.4948496 0.3352870 1.0000000 0.1645225 0.2462188

f1cncpt2 0.1791069 0.1383291 0.1645225 1.0000000 0.5898973

f1locus2 0.2474076 0.2032299 0.2462188 0.5898973 1.0000000

These correlations are close to the ones in the table, but not quite

right. Perhaps it would be more sensible to use complete observations

across the board, as these are the ones that will be included in the

regression analysis.

> cor(grades1, use="complete.obs")

f1txhstd byses bygrads f1cncpt2 f1locus2

f1txhstd 1.0000000 0.4299589 0.4977062 0.1727001 0.2477357

byses 0.4299589 1.0000000 0.3254019 0.1322685 0.1942161

bygrads 0.4977062 0.3254019 1.0000000 0.1670206 0.2283377

f1cncpt2 0.1727001 0.1322685 0.1670206 1.0000000 0.5854103

f1locus2 0.2477357 0.1942161 0.2283377 0.5854103 1.0000000

That did it! I'm going to fix those variable names now because, seriously? The

variables, in order, are standardized achievement scores, family socioeconomic

status, previous grades, a self esteem score, and a locus of control score.

(Locus of control tells how you feel your life is governed, internally by

yourself, called internal locus of control, or externally by forces beyond

your control, called external locus of control. Higher scores generally indicate

a more external locus of control on these scales, and I assume the same is true

in this case, although I'm not certain.)

> colnames(grades1) = c("std.achieve.score","SES","prev.grades","self.esteem","locus.of.control")

> head(grades1)

std.achieve.score SES prev.grades self.esteem locus.of.control

1 61.71 -0.563 3.8 -0.10 -0.14

2 46.98 0.123 2.5 -0.45 -0.58

3 50.48 0.229 2.8 0.33 -0.59

4 56.48 0.687 3.5 -0.02 0.07

5 55.32 0.633 3.3 -0.09 -0.85

6 39.67 0.992 2.5 -0.28 0.07

I feel much better now! The first analysis is a standard regression analysis

(shown in Figure 5.2, page 77). I'm going to use a trick in the regression

model formula, DV~., which means DV as a function of all other variables.

> lm.out = lm(std.achieve.score ~ ., data=grades1)

> summary(lm.out)

Call:

lm(formula = std.achieve.score ~ ., data = grades1)

Residuals:

Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

-24.8402 -5.3648 0.2191 5.6748 20.3933

Coefficients:

Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

(Intercept) 35.5174 1.2256 28.981 <2e-16 ***

SES 3.6903 0.3776 9.772 <2e-16 ***

prev.grades 5.1502 0.3989 12.910 <2e-16 ***

self.esteem 0.2183 0.5007 0.436 0.663

locus.of.control 1.5538 0.5522 2.814 0.005 **

---

Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

Residual standard error: 8.041 on 882 degrees of freedom

(113 observations deleted due to missingness)

Multiple R-squared: 0.3385, Adjusted R-squared: 0.3355

F-statistic: 112.8 on 4 and 882 DF, p-value: < 2.2e-16

> confint(lm.out) # confidence intervals for the regression coefficients

2.5 % 97.5 %

(Intercept) 33.1120344 37.922735

SES 2.9491568 4.431499

prev.grades 4.3672598 5.933147

self.esteem -0.7643607 1.201002

locus.of.control 0.4700688 2.637597

Spot on, so far. Good job, SPSS! We have not yet duplicated the ANOVA table

or the beta coefficients.

> print(anova(lm.out), digits=7)

Analysis of Variance Table

Response: std.achieve.score

Df Sum Sq Mean Sq F value Pr(>F)

SES 1 15938.64 15938.645 246.49535 < 2.22e-16 ***

prev.grades 1 12344.62 12344.616 190.91274 < 2.22e-16 ***

self.esteem 1 391.62 391.623 6.05655 0.0140453 *

locus.of.control 1 512.00 512.001 7.91823 0.0050028 **

Residuals 882 57031.03 64.661

The anova() broke the regression SS into four

parts. If we sum them, we get the regression SS in the SPSS table. That seems

like a lot of work, so let's get the total SS and then get the regression SS

by subtraction. The first thing I'm going to do is write a function to calculate

sum of squares when there are missing values.

> SS = function(x) sum(x^2,na.rm=T) - sum(x,na.rm=T)^2 / sum(!is.na(x))

> SS(grades1$std.achieve.score)

[1] 91124.93

Fail! Why? Because achievement scores were included in this calculation

that were not included in the regression analysis. The perils of missing values!

There are 77 missing

achievement scores, more than any of the other variables, but apparently

there were some achievement scores present that were paired with missing

values in other variables. Since those were not included in the regression

analysis, we don't want them in this calculation either. The simplest thing

to do is to create a new data frame with cases that have missing values

omitted. We will then have only the complete cases that were used in the

regression. (This might not have been a bad idea right from the get go!)

> grades2 = na.omit(grades1)

> SS(grades2$std.achieve.score) # total SS

[1] 86217.92

Better.

> SS(grades2$std.achieve.score) - 57031.03 # regression SS

[1] 29186.89

R and SPSS disagree a tad on the rounding, but I think we can let that slide.

Now let's get the beta coefficients. To do that, we're going to use the

scale() function to convert the entire numeric

data frame to z-scores. The output is a matrix, so we have to convert it to

a data frame before we can use it in the regression analysis.

> grades3 = scale(grades2)

> grades3 = as.data.frame(grades3)

> coef(lm(std.achieve.score~SES+prev.grades+self.esteem+locus.of.control, data=grades3))

(Intercept) SES prev.grades self.esteem

-3.264896e-16 2.854706e-01 3.802391e-01 1.474298e-02

locus.of.control

9.683904e-02

Spot on, although that may have been a little more work than some of you

were hoping for. Still, I think it's easier than hunting and pecking your way

through a dozen menus to get it done!

Just A Touch Of Theory

Before we do the hierarchical regression, let's talk a little about what

the hierarchical regression does that the standard regression does not. I

think Keith's exposition on this is so clear that I'm going to essentially

paraphrase it, and I'll refer you to his textbook for more. (He covers

hierarchical regression only briefly, but it is an excellent summary.)

Standard regression enters all of the predictor variables at once into the

regression, and each predictor is treated as if it were entered last. That is,

each predictor variable in the regression table above is controlled for all of

the other predictors in the table. Thus, we can say that the effect of SES is

3.6903 when prev.grads, self.esteem, and locus.of.control are held constant

or are held at their mean values.

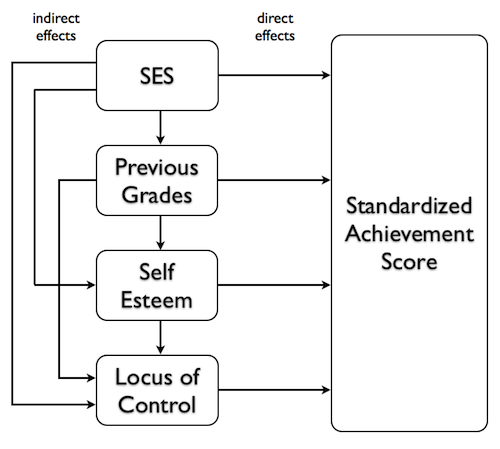

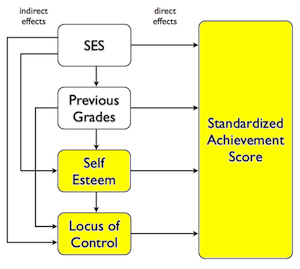

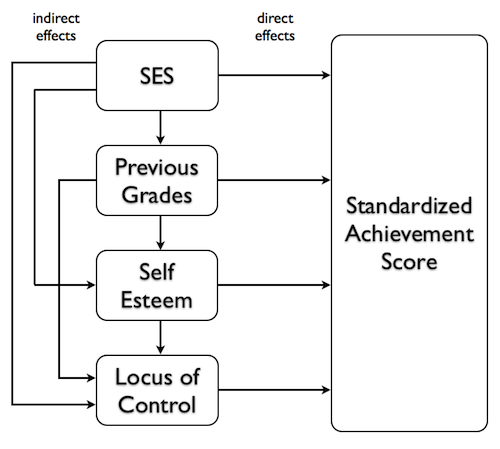

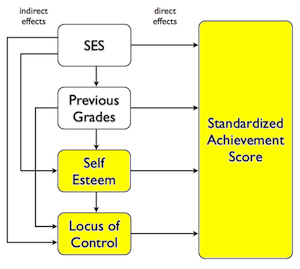

The following diagram, which I have redrawn from Keith (Figure 5.7, page 83),

shows what this means most clearly.

In the little regression universe that we've created for ourselves, the

predictors can influence the response potentially over several pathways. For

example, SES can have a direct effect on achievement scores, indicated by the

arrow that goes straight to the response, but it can also have effects that

follow indirect pathways. It can have an effect on locus of control, which

then affects achievement scores. It can have an effect on self esteem, which

can then act directly on achievement scores, but can also act through locus

of control. Following the other arrows around (other than the arrows showing

direct effects) will show us how WE THINK each of these predictors might have

an indirect effect on achievement scores.

Standard regression reveals only the direct effects of each predictor.

Because SES is treated as if it is entered last in a standard regression, all

of the indirect effects of SES have already been pruned away, having been

handed over to one of the other predictors, before SES gets to attempt to

claim variability in the response. Thus, SES is left only with its direct

pathway.

However, if SES were entered alone into a regression analysis (as

the only predictor, that is), we would get to see its total effect on

achievement score, which is its effect through both direct and indirect

pathways, because it wouldn't be competing with the other predictors for

response variability.

That's what a hierarchical regression does. If SES were entered first into

a hierarchical regression, it would get to claim all the response variability

it could without having to compete with the other predictors. In other words,

we wouldn't be seeing just the direct effect of SES on achievement scores, we'd

be seeing the total effect. Then when we enter Previous Grades second, we'd

get to see its total effect, provided none of that effect goes through SES and,

therefore, has already been claimed. Then we enter Self Esteem third, and we

see it's total effect, provided none of that goes through either Previous

Grades or SES. And so on.

In other words, standard regression reveals direct effects only. Hierarchical

regression reveals total effects, provided we have entered the predictors in

the correct order. And that is a BIG provided! Order of entering

the predictors is the biggest catch in hierarchical regression. How do we know

what order to use? Keith recommends drawing a diagram like the one above. Such

a diagram should make it clear in what order the variables should be entered.

If you can't draw such a diagram, then you probably shouldn't be using

hierarchical regression.

Note: I have to admit that it helped me a lot to have already written the

tutorial on Simple Mediation Analysis when I was

attempting to understand this!

Now For The Hierarchical Regression

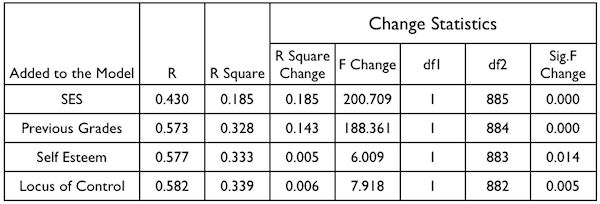

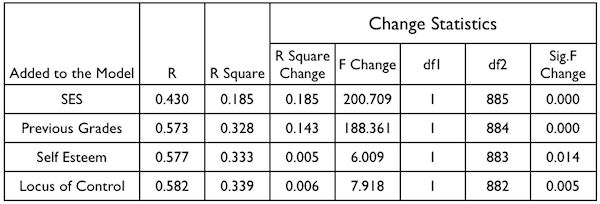

Here are the hierarchical (or sequential as Keith calls it) multiple

regression results (Figure 5.3, page 79) as SPSS (I assume) calculated them.

The variables were entered one at a time in the order shown in the table.

We already have some of these results. We need to recall the total sum of

squares, 86217.92, and we need to recall the ANOVA table we produced earlier.

> print(anova(lm.out), digits=7)

Analysis of Variance Table

Response: std.achieve.score

Df Sum Sq Mean Sq F value Pr(>F)

SES 1 15938.64 15938.645 246.49535 < 2.22e-16 ***

prev.grades 1 12344.62 12344.616 190.91274 < 2.22e-16 ***

self.esteem 1 391.62 391.623 6.05655 0.0140453 *

locus.of.control 1 512.00 512.001 7.91823 0.0050028 **

Residuals 882 57031.03 64.661

We can get the change in R-squared values by dividing each SS by the total.

> c(15938.64, 12344.62, 391.62, 512.00) / 86217.92

[1] 0.184864585 0.143179283 0.004542211 0.005938441

Of course, the R Square column is just the cumulative sum of those.

> cumsum(c(15938.64, 12344.62, 391.62, 512.00) / 86217.92)

[1] 0.1848646 0.3280439 0.3325861 0.3385245

And if you want to be really anal about it, the R column is the square root

of that.

> sqrt(cumsum(c(15938.64, 12344.62, 391.62, 512.00) / 86217.92))

[1] 0.4299588 0.5727511 0.5767028 0.5818286

Notice that our ANOVA table does not give the same tests, however (except for

the last one). Why? The answer is that the ANOVA table tests are done with a common

error term, namely, the one shown in the table. The tests in the SPSS table

can be obtained from the ANOVA for any term by pooling all the terms below it

in the table with the error term. For example, the test for prev.grades would be:

> ((12344.62)/1) / ((391.62+512.00+57031.03)/(1+1+882)) # F value

[1] 188.3613

> pf(188.3613, 1, 884, lower=F) # p-value

[1] 5.310257e-39

We could also do that like this, but ONLY the prev.grades test is available

in this output.

> anova(lm(std.achieve.score ~ SES + prev.grades, data=grades2))

Analysis of Variance Table

Response: std.achieve.score

Df Sum Sq Mean Sq F value Pr(>F)

SES 1 15939 15938.6 243.20 < 2.2e-16 ***

prev.grades 1 12345 12344.6 188.36 < 2.2e-16 ***

Residuals 884 57935 65.5

---

Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

Which tests are correct, the tests in R's ANOVA table, or the tests in the

SPSS table?

What Is The Correct Error Term?

According to every textbook I've ever read, and that's at least a couple,

the SPSS tests are correct. This is not a trivial point, because there are

multiple forums and R blogs online that advise doing a hierarchical regression

like this.

> model1 = lm(std.achieve.score ~ 1, data=grades2)

> model2 = lm(std.achieve.score ~ SES, data=grades2)

> model3 = lm(std.achieve.score ~ SES + prev.grades, data=grades2)

> model4 = lm(std.achieve.score ~ SES + prev.grades + self.esteem, data=grades2)

> anova(model1, model2, model3, model4, lm.out)

Analysis of Variance Table

Model 1: std.achieve.score ~ 1

Model 2: std.achieve.score ~ SES

Model 3: std.achieve.score ~ SES + prev.grades

Model 4: std.achieve.score ~ SES + prev.grades + self.esteem

Model 5: std.achieve.score ~ SES + prev.grades + self.esteem + locus.of.control

Res.Df RSS Df Sum of Sq F Pr(>F)

1 886 86218

2 885 70279 1 15938.6 246.4953 < 2.2e-16 ***

3 884 57935 1 12344.6 190.9127 < 2.2e-16 ***

4 883 57543 1 391.6 6.0566 0.014045 *

5 882 57031 1 512.0 7.9182 0.005003 **

---

Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

Notice that this exactly duplicates the results that are in the ANOVA table and

not those in the SPSS table. To duplicate the results that are in the SPSS

table, you would have to make these model comparisons two models at a time.

For example...

> anova(model2, model3)

Analysis of Variance Table

Model 1: std.achieve.score ~ SES

Model 2: std.achieve.score ~ SES + prev.grades

Res.Df RSS Df Sum of Sq F Pr(>F)

1 885 70279

2 884 57935 1 12345 188.36 < 2.2e-16 ***

---

Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

...would give the correct test for prev.grades. Or just...

> anova(model3) # not shown

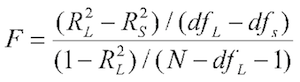

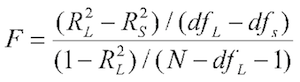

...for the prev.grades test ONLY. So who says SPSS is right? Well, pretty

much everybody! The formula given for comparing two nested regression

analyses in every textbook I've consulted is this one, where for some

unaccountable reason L stands for the full model and S the reduced model.

(Maybe it means "larger" and "smaller." Didn't think of that!)

That this is the equivalent of the SPSS tests is easily demonstrated. To

test the effect of adding self.esteem to the model, for example, we would need

to know that the change in R-squared was .0045422, that the change in df was 1,

that R-squared for the full model, including self.esteem, was .33259, and N

was 887, after dropping all the cases with missing values. So...

> .0045422/((1-.33259)/(887-3-1)) # F-value

[1] 6.009443

Since there is no function in R that automates a hierarchical regression, the

lesson here is BE CAREFUL WITH THE ERROR TERM.

Entering Variables In Blocks

Variables don't have to be entered one at a time into a hierarchical

regression. They can also be entered in blocks. This might happen, for example,

if the researcher wanted to enter all psychological variables at one time, or

if the researcher was uncertain about the order in which they should be entered.

Let's say in the current example we wanted to enter self.esteem and

locus.of.control at the same time. (Frankly, I was unconvinced by Keith's

argument concerning the order in which these variables should be entered.)

The increase in R-squared can be obtained by summing the SSes in the ANOVA

table and dividing by the total SS.

> (391.62 + 512.00) / 86217.92

[1] 0.01048065

Which is just the sum of the individual increases in R-squared. The test on

this would be the following.

> anova(model3, lm.out)

Analysis of Variance Table

Model 1: std.achieve.score ~ SES + prev.grades

Model 2: std.achieve.score ~ SES + prev.grades + self.esteem + locus.of.control

Res.Df RSS Df Sum of Sq F Pr(>F)

1 884 57935

2 882 57031 2 903.62 6.9874 0.0009754 ***

---

Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

Model 3 was the model before this block of variables was entered, i.e., the

model that included SES and prev.grades, and lm.out was the model after this

block of variables was entered. This is in agreement with the SPSS output that

is in Figure 5.9 in Keith. So, good, SPSS got it right again!

Question

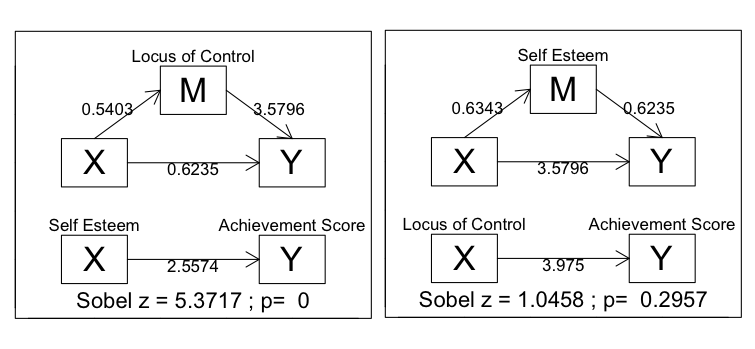

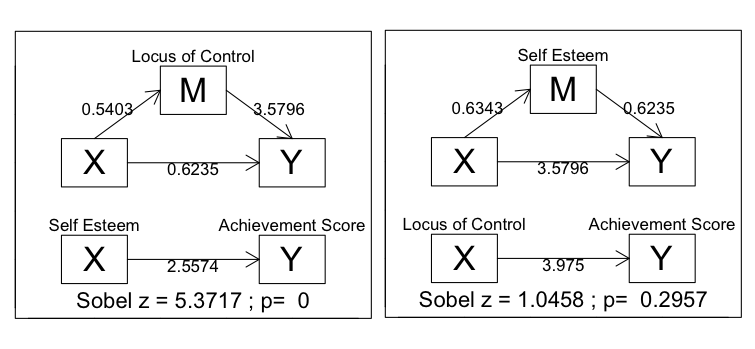

I couldn't help noticing how much the shaded portion of the NELS diagram at

left resembles a Simple Mediation Analysis, or

rather, the diagram one would draw to represent such an analysis. As I said

above, I'm not convinced Keith got self.esteem and locus.of.control in the

correct order in the hierarchical regression. I believe the order should be

reversed. I believe locus.of.control, being something that is learned from

your environment, is the causally prior (or at least more important) variable.

(Not being an expert on either of these constructs, I doubt that my "belief"

should carry much weight, and I'm just playing devil's advocate!) So the

mediation analysis people should

forgive me, but I decided to play a little fast and loose with a mediation

analysis. My "hypothesis" (such as it is) is that, if locus of control is

entered as the mediator, it will completely sap self-esteem of its effect on

achievement scores (complete mediation), because it's locus of control that's

having the effect on scores and not self-esteem. That relationship would not

be seen in the hierarchical regression as we've done it, because by the time

locus of control got into the model, self-esteem has already grabbed a large

(and undeserved) piece of the pie. Locus of control has been short circuited,

so to speak. On the other hand, if the roles of self-esteem

and locus of control were reversed in the mediation analysis, i.e., self-esteem

entered as the mediator, we'd see virtually no mediation. I did those two

analyses using the mediate() function that is

discussed in the mediation analysis tutorial. The results are in the following

diagrams (created by that function). The numbers on the lines are regression

coefficients from the various models used to do the mediation analysis (see

that tutorial).

For the record, these were the commands used. The

mediate() function is in the tutdata folder that you may have

downloaded to accompany these tutorials.

For the record, these were the commands used. The

mediate() function is in the tutdata folder that you may have

downloaded to accompany these tutorials.

> with(grades2, mediate(self.esteem, std.achieve.score, locus.of.control,

+ names=c("Self Esteem","Achievement Score","Locus of Control")))

a b c cp sobel.z p

0.540276 3.579580 2.557419 0.623457 5.371740 0.000000

> with(grades2, mediate(locus.of.control, std.achieve.score, self.esteem,

+ names=c("Locus of Control","Achievement Score","Self Esteem")))

a b c cp sobel.z p

0.634315 0.623457 3.975048 3.579580 1.045782 0.295662

It appears my "hypothesis" was confirmed. Pretty close anyway. My question

is, what does it mean? Does it mean I'm right and these variables

were entered in the wrong order in the hierarchical regression? Does it

mean the opposite? Or do the two analyses bear no relationship to one

another?

I don't know the answers to these questions, and I suspect they are not to

be found in the above analyses. That's why we are constantly warned that

techniques like these (hierarchical regression, mediation analysis, path

analysis) are not useful for exploratory analyses. These are correlational

data, and as we know, we can twist correlational data around our little

fingers and make them do just about anything we want. Also, there is no

guarantee that these are the only variables, or even the most important

variables, that we should be looking at.

This is one case where the hard work should definitely come BEFORE the

analysis. It's up to us to be familiar enough with the phenomena under

investigation that we can form reasonable and rational theories of causation.

We CANNOT get those from correlational data. Correlational data can be

consistent or inconsistent with our previously formed theories, but that's

all. There is a much quoted warning (concerning path analysis, but equally

applicable to any of these similar techniques) from Everitt and Dunn (1991)

that is worth repeating here: "However convincing, respectable and reasonable

a path diagram... may appear, any causal inferences extracted are rarely more

than a form of statistical fantasy."

- Everitt, B. S. and Dunn, G. (1991). Applied multivariate data analysis.

London: Edward Arnold.

created 2016 March 29

| Table of Contents

| Function Reference

| Function Finder

| R Project |

|