The Panopticon

The Panopticon refers to a design for a prison in which a prisoner cannot tell whether or not the guard is currently watching them. As a consequence, the prisoner theoretically will self-regulate their own behavior. This philosophical model, contrived by British philosopher Jeremy Bentham in the late 18th Century, is a useful analogy for the type of environment that can be created by mass government and private sector surveillance.

Video Lecture

Jeremy Bentham’s Prison

Jeremy Bentham was a British philosopher who lived from 1748 to 1832. Although he was trained as an attorney, he became frustrated with the arcane state of the law at the time and instead spent most of his life campaigning for various social and legal reforms.1

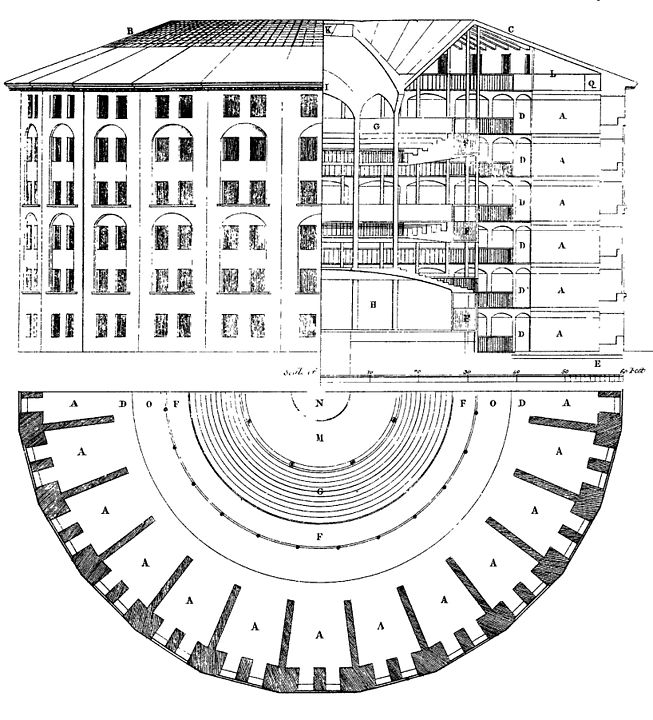

In the late 1700s, Bentham designed a prison that could, in theory, be staffed with a single guard. The basic idea behind this design is that all the prisoners would be placed at the perimeter of the facility, while the guard would be in a central compartment that would permit the guard to see the prisoners, without the prisoners being able to see the guard (see Figure 1).

Several prisons were designed based on Bentham’s Panopticon, although most of them have subsequently been abandoned. One example was the Presidio Modelo in Cuba (Figure 2).

Bentham’s intent with this centralized design was reduce the number of prison staff required. Since no prisoner could know at any given time whether or not the guard was watching, prisoners theoretically would be more likely to regulate their own behavior on the chance the guard might observe them breaking the rules. Of course, the prisoners were in prison in the first place for failing to regulate their own behavior, which might explain why physical panopticon designs have been abandoned in practice.

The Digital Panopticon

The Netherlands has revived the literal panopticon concept using technology to monitor the inmates at Detention Concept Lelystad. Here, the prisoners are monitored using a combination of electronic wristbands, cameras, and audio surveillance. Emotion recognition software is employed to detect violence and signs of other behavioral issues. This approach to incarceration claims to reduce guard staffing by over 50% and total costs per prisoner by 30%.4

However, there is a more widespread implementation of the digital panopticon that affects everyone who isn’t in prison. Governments are finding surveillance-based implementations of this model to be useful for maintaining law, order, and control. Since no staff of government agents can monitor all citizens all the time, technology can instead be used to monitor an individual’s communications, whereabouts, movements, and habits. For example, the National Security Agency is believed to be recording nearly all electronic communications inside the United States, including phone calls, text messages, emails, Internet searches, and various other digital artifacts.5

The Private Sector

Although Jeremy Bentham’s panopticon prison design may have been intended for a government audience, he actually borrowed the underlying idea from his brother Samuel. Samuel Bentham’s application of this design was not for a prison but instead was a way for an experienced manager to supervise relatively unskilled workers.6 In a twist of irony, the modern-day digital panopticon also involves the private sector.

Companies today are always looking for new revenue streams, and the sale of private data is a lucrative source of sustainable cash flow. Entire categories of consumer goods are now being offered with online connectivity, regardless of whether or not such features actually make any practical sense. For example, both microwaves and conventional ovens are available in models that have wireless connectivity. Some of these devices connect to servers located in Russia and China.7 While marketing departments might create narratives to drive the popularity of such connected devices, data collection is likely an underlying motivation.

With numerous companies collecting vast amounts of information about individuals, an even larger panopticon is created in several different dimensions. First, anything the private sector collects is easily obtainable by a government. In the United States, for instance, a subpoena (which doesn’t require judicial oversight) is often sufficient to compel a company to turn over information about an individual. Since company-held information is normally considered to be a “business record,” there often isn’t a need to obtain a warrant to compel disclosure. This ability for the government to tap into private sector data expands the size of the digital panopticon beyond what the NSA could create on its own.

A second dimension of a panopticon is created by the companies themselves, particularly social media providers. Since so much information is available about individuals these days, it is possible to determine a person’s associations, attitudes, and opinions by reading their social media posts and those of their friends. In today’s cancel culture, simply associating with someone who has an unpopular opinion or has engaged in detestable actions is sufficient to create popular blame that spreads to bystanders. A panopticon-like effect occurs when people begin censoring their opinions or curating their friend associations to avoid a negative appearance.

Finally, a third dimension of panopticon is created unintentionally by the private sector. Each company collecting, processing, or storing data about individuals becomes a lucrative target for malicious actors such as identity thieves and extortionists. If a bad actor can compromise a company’s systems and steal information about individuals, then threats to disclose that information can be made against both the company and each individual whose data have been stolen, demanding ransoms in the process. Alternatively, the stolen data could simply be published, expanding the second dimension of the panopticon fueled by popular opinion.

References and Further Reading

-

University College London. About Jeremy Bentham ↩

-

Image source: Wikimedia Commons (User: DieBuche). [Public Domain] ↩

-

Image source: Wikimedia Commons (User: Friman). [CC-BY-SA] ↩

-

Toby Sterling. Dutch open Big Brother-style prison. The Guardian. January 18, 2006. ↩

-

Electronic Frontier Foundation. How the NSA’s Domestic Spying Program Works ↩

-

University College London. The Panopticon ↩

-

Thomas Claburn. Smart ovens do really dumb stuff to check for Wi-Fi. The Register. January 26, 2023. ↩