VPN Services

One way to prevent an Internet Service Provider from tracking the sites a user visits is to use a Virtual Private Network (VPN) service. A VPN service fully encrypts Internet traffic as it leaves the user’s computer or home network, limiting what the ISP is able to determine about the user’s activities. However, commercial VPN services are not without issues, and the market is full of questionable providers and shady business practices.

Video Lecture

Hiding from the Internet Service Provider

Recall from the previous lesson that there are 3 major privacy issues with Internet Service Providers (ISPs) in the United States:

- The ISP sees everything.

- The ISP can sell everything.

- The ISP can retain data indefinitely.

Since American ISP’s frequently have local monopolies, there often isn’t a realistic choice for an alternative provider. Even in situations where an alternative provider exists, its performance might not be as good, and its privacy practices might not be any better in comparison. Since an ISP can collect anything it can observe, maintaining privacy from the ISP is only possible if it cannot make sense of anything it does observe. The way to implement this protection is to encrypt all traffic.

As we have previously seen, the Secure Hypertext Transfer Protocol (HTTPS) has a major weakness in its current implementation and leaks the website the user is visiting in cleartext. In addition, most connections to Domain Name System (DNS) servers are made entirely without encryption. While it is possible to encrypt DNS connections with DNS over HTTPS (DoH), it isn’t currently possible to close the HTTPS information leak caused by Server Name Indication (SNI). Therefore, an ISP can still see every website a subscriber visits.

One way to hide this information from the Internet Service Provider is to use a Virtual Private Network (VPN) service. With a VPN service, all network traffic is encrypted between the user and the VPN provider. The ISP can see that the user is connected to a VPN provider, but they will only see indecipherable encrypted data passing over the connection. If the user is browsing the World Wide Web over a VPN, then the ISP cannot see which websites are being visited by monitoring the cleartext part of the HTTPS connection process. Since DNS queries are also sent over the VPN to a third-party DNS server, the ISP cannot gain information about the user from the DNS lookups, either.

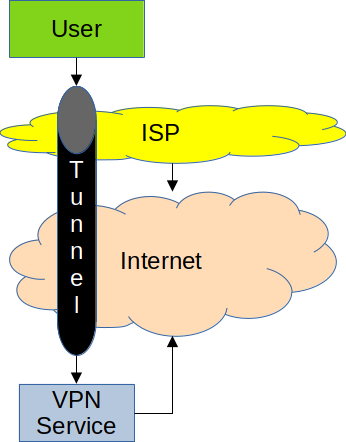

Using a VPN to Tunnel Traffic

When a user connects to a VPN service, an encrypted tunnel is established between the user’s device and the service (Figure 1). When browsing the Web while using the VPN connection, all traffic – including DNS queries and HTTPS connections – is sent through the tunnel to the VPN service provider. The VPN service provider then routes the connections over the Internet to the destination servers. Since the tunnel is encrypted, the Internet Service Provider cannot see the contents of the traffic and therefore cannot monitor the user’s browsing habits. However, the tunnel does have to cross the ISP’s network and the Internet to reach the VPN service provider. Therefore, the ISP can see that the user is connected to a VPN service. The ISP cannot, however, see what the user is doing with that service.

At first glance, this appears to be a magic solution to the privacy problems with the Internet Service Provider. However, while using the VPN tunnel effectively hides the traffic from the ISP, the traffic is not hidden from the VPN service provider. It cannot be hidden, since the VPN service provider has to know where to send it on the Internet. Therefore, the privacy threat is shifted from the ISP to the VPN service:

- The VPN service sees everything.

- The VPN service can sell everything (unless it is based in a country with laws to the contrary).

- The VPN service can potentially retain data indefinitely.

Fortunately, there is meaningful competition among VPN service providers. In contrast to Internet Service Providers, users have choices, since the VPN service choices are not determined by the user’s physical address. That said, the VPN service industry is rife with dishonesty and deceptive trade practices, so caveat emptor (buyer beware).

Dishonesty in the VPN Service Industry

Dishonest marketing practices are absolutely rampant in the VPN service industry. Scare tactics are used to convince potential purchasers to sign up for a service, often accompanied by high-pressure sales techniques. Dark patterns trick users into paying for services to which they didn’t intend to subscribe while also making it difficult to cancel an unsatisfactory service. The security and privacy capabilities of a VPN are frequently overstated.1 Affiliate marketing practices in the VPN industry lead to a proliferation of phony reviews and recommendations. Furthermore, all VPN services claim not to log any user activities, but records from court cases prove otherwise.

Scare Tactics

Many Virtual Private Network service providers capitalize upon fear in the designs of their websites. If one visits the site of a typical VPN service without using a VPN, there is often some kind of scary message (in red lettering) informing the user that they are “unprotected.” A user who signs up for that VPN service and then visits the service provider’s website will instead see a message that says they are “protected,” usually in green lettering. This is a dishonest practice, since there isn’t anything special going on from a technological perspective. The VPN service doesn’t have some magic insight into the user’s browser or system configuration. Instead, the service simply displays the “protected” message when the user is connected to the VPN provider’s website through that provider’s service. Connecting to the website without a VPN – or indeed, connecting to the website using a competitor’s VPN – will render the “unprotected” message.

Another scare tactic commonly employed by VPN providers is to display the geographic location from which the user is connecting. For example, a user connecting to a VPN provider directly from Coastal Carolina University might see a “Conway, South Carolina, USA” message next to the “unprotected” message. Once again, there is nothing informative about this message. Since IP addresses are allocated to Internet Service Providers (and universities) in blocks, there are databases that map IP address ranges to approximate geographical location (city, state, and country). Some of these databases are freely available to any website operator.2

Dark Patterns

Some Virtual Private Network services intentionally design their websites to be tricky or confusing to use. These so-called dark patterns include design elements that make it more likely for the user to click on a function that does the opposite of what the user intended. For example, a user might try to cancel a service only to be greeted by a page that instead renews the service if the prominent confirmation button is clicked. Careful reading of the page is necessary to detect such a design, and finding the working cancellation link in small text buried somewhere on the page requires considerable time and effort.

A related set of design issues with VPN service provider sites is the use of high-pressure sales tactics and misleading site mechanisms. Some popular VPN service providers employ a countdown timer on the service website that indicates when a “sale” will end, and the price will increase for the service if the user doesn’t sign up within a short window. Most such sites run the same “sale” every day, and the “discounted” price is actually the normal price that most users pay for the service.

Exaggerated Claims

VPN service providers tend to make exaggerated privacy claims about the capabilities of their services, even going so far as to state or imply that the VPN service will make the user “anonymous” on the Internet.1 However, this claim isn’t even slightly true. First, many users log into various websites with a username and password, which they will continue to do over the VPN connection. If a user is logged into a website, anything they do on that site (or on any site with shared tracking mechanisms) is tied to them regardless of whether or not a VPN is used. Second, a VPN service only encrypts the tunnel between the user and the VPN service provider. It is straightforward for an observer to see which VPN service provider is in use. If that observer is a government entity, it is equally straightforward to compel the VPN service provider to turn over information about the user’s activities.

Many VPN services claim to “protect” the computer from various kinds of malware, viruses, and other threats.1 This “protection” is negligible at best and counterproductive at worst. Since many VPN providers supply their own custom software applications for connecting to the VPN, there is an extra security attack surface created by that application. No significant piece of computer software is completely bug free, so running an extra application that contains a vulnerability would actually make security worse. Even in the best case scenario, block lists employed by VPN service providers to try to protect users from security threats are likely not much better than the ones already used by the Web browser.

Affiliate Marketing and Phony Reviews

The vast majority of Virtual Private Network service providers employ affiliate marketing techniques to grow their subscriber counts. In an affiliate marketing arrangement, a content creator – such as the author of a website or the creator of a YouTube video – is paid a commission for each new user that signs up for the VPN service. A content creator who can influence more people to sign up for a given service therefore earns more money from the affiliate marketing arrangement. Many VPNs will have an “affiliate” or “partner” link on their websites that can be used to detect the presence of these programs. However, some VPN services do a better job of concealing this marketing practice and hide the affiliate information on a separate website.3

Affiliate marketing leads to several undesired outcomes in the VPN service space. First, running a VPN service costs money. There are bandwidth charges for all the traffic passing through the VPN, servers to rent or buy, staff to pay, lawyers to pay, and various other costs. In addition, the VPN space is competitive, with multiple companies all driving prices to the lowest possible point. The entire space is therefore ripe for overselling the same capacity while underprovisioning the servers and network links. Taking a substantial portion of funds and directing it into affiliate marketing only further reduces the money actually spent on providing the service. The net result is that VPN services that spend a lot on marketing may have poor performance, which may be (incorrectly) blamed on the extra latency of passing through the VPN servers. In reality, while the latency is indeed higher, the connection throughput is also substantially lower, since the services are oversold.

The other major problem that affiliate marketing creates is a proliferation of phony VPN service review sites. A quick Web search for VPN services often yields pages containing lists of the “top” VPN services, sometimes sorted by year, by month, or by purpose. Given the perverse incentives created by affiliate marketing arrangements, it should come as no surprise that the “rankings” on these pages are sometimes in order of decreasing affiliate payouts, with the best-paying affiliate ranked as number one.4 A second major problem with these phony review sites is that they tend to include one review per service. However, a number of companies own and operate multiple VPN services.5 Some services are therefore simply different brand names for the same product, leading to duplicate entries on the review lists.

Government Cooperation

Despite some VPN services’ claims of absolute privacy, these services are required to comply – and will comply – with legal orders.6 From a government surveillance perspective, VPN services might even make a user more attractive to the intelligence community. For example, international intelligence alliances such as Five Eyes result in information sharing among nations.7 This multinational cooperation enables governments to bypass their own domestic privacy laws that are designed to protect their own citizens from surveillance.8 Since VPN providers represent a relatively small footprint when compared to all Internet traffic, it would be easier for an intelligence agency to monitor the set of all VPN servers than it would be to monitor every user on the Internet.

“No Logs”

Just about every VPN service provider in existence claims not to log user activities. However, there is no effective way to verify that no logs are being kept. Even if the VPN service is “audited” by a third party, there is no guarantee that the audit isn’t phony or that the third party performed the audit correctly. It is difficult to run a networked computing system consisting of multiple servers without maintaining at least some level of logging (speaking from experience). Even if service logs are somehow avoided, the VPN applications could contain logging, analytics, or telemetry code that monitors the user at the device level.9

There are readily available examples in federal court records showing that VPN services log user activities. In one case, a sworn affidavit from an investigator demonstrated that the PureVPN service was able to identify a subscriber when given the VPN service IP address the subscriber used.10 Nevertheless, the PureVPN website claims they “never log[] your data.”11 In another case, a sworn affidavit shows that Highwinds Network Group was able to identify a user given the IP address and port number of an Internet Relay Chat (IRC) server that was visited from someone using the VPN service.12 Highwinds is the parent company of IPVanish, StrongVPN, and the apparently discontinued Encrypt.me services (and has since been acquired by another, larger provider with even more service offerings).5 A quick visit to IPVanish shows a claim of “no logs”,13 while StrongVPN claims “zero logging.”14 None of these services would have been able to identify the suspects in these cases had no logs been kept, since there would not have been an easy way to associate a user account with specific activity. Therefore, user logs must have been created and retained.

Evaluating VPN Service Providers

Selecting a VPN service that is honest, or is at least less dishonest than its competitors, requires quite a bit of effort. It is important not to rush into any service or to fall victim to any marketing hype. A diligent process is required to find VPN services that would be suitable to use as a means of increasing privacy online. It is a good idea to consider the following:

- Try to find a VPN provider that does not have any type of affiliate marketing program or similar revenue-sapping gimmicks. Affiliate marketing makes unbiased reviews impossible. In addition, gimmicks such as free trials or a free service tier cost the company money, which they have to make up from additional paid subscriptions, from participating in the surveillance economy, by overselling the service, or by some combination of these things. Note that some providers attempt to hide affiliate programs, so some searching is necessary if one cannot be located from the provider’s website.

- Look for a provider that is based in a country that has a national privacy law. European countries tend to have an advantage due to the General Data Protection Regulation, but they are not the only possible countries. Avoid providers in the United States, as there is no national privacy law here.

- Evaluate the provider’s website. Avoid providers that make extensive use of dark patterns, scare tactics, offer countdown timers, and other high-pressure sales techniques.

- Look for a VPN service that does not require an email address or any other type of personal information to create an account. Creating an account should be a random process that yields some kind of account number or credential. There should be no simple way to associate the account with any individual. Note that the payment method can create an association, particularly if a credit card is used. Look for a service that accepts cash, sells retail scratch-off cards that do not have serial numbers, or perhaps supports some types of cryptocurrency (but be careful using crypto).

There are few providers that can meet all these criteria. As of the last update to this page, IVPN15 and Mullvad VPN16 are the only two I have seen. Note that the course associated with this page is normally taught in the spring semester, so expect updates about once per year. You will need to do your own research here!

Finally, the fourth recommendation might seem extreme for selecting a VPN service for personal, legal use. However, it is important to consider that VPN providers are companies. Companies are periodically bought and sold. If the VPN provider is sold to an advertising technology company, an email address or other way to link any logged activity back to an individual is simply a way for that new parent company to add information to a person’s advertising profile. Or, to put it another way, a VPN service that can associate browsing activity with an individual simply becomes another Internet Service Provider. Having two ISPs layered on top of one another is silly. The whole point of using a VPN is to hide traffic from the ISP, and the ISP is still necessary to connect to the VPN. Therefore, it is best if the VPN provider does not link the VPN account to an individual.

References and Further Reading

-

Dennis Schubert. “VPN - a Very Precarious Narrative.” April 8, 2019. ↩↩↩

-

Proton. “Join our Partners Program.” ↩

-

Jonah Aragon. “The Trouble with VPN and Privacy Review Sites.” Privacy Guides. November 20, 2019. ↩

-

Jan Youngren. “Who owns your VPN? 105 VPN products run by just 24 companies.” The VPNpro Blog. March 17, 2023. ↩↩

-

Michael Kan. “NordVPN: Actually, We Do Comply With Law Enforcement Data Requests.” PCMag. January 19, 2022. ↩

-

James Cox. “Canada and the Five Eyes Intelligence Community.” Strategic Studies Working Group Papers. Canadian International Council. December 2012. Available from the Internet Archive ↩

-

Hubert Seipel. “Snowden-Interview in English.” Norddeutscher Rundfunk. January 26, 2014. Available from the Internet Archive ↩

-

Craig Silverman. “Popular VPN And Ad-Blocking Apps Are Secretly Harvesting User Data.” BuzzFeed News. March 9, 2020. ↩

-

United States of America v. Ryan S. Lin (1:18-cr-10092). District Court, D. Massachusetts. Affidavit of FBI Special Agent Jeffrey Williams. October 3, 2017. Available from the Department of Justice ↩

-

United States of America v. Vincent Gervirtz (1:16-mj-00487). District Court, S.D. Indiana. Affidavit of DHS Special Agent Michael Johnson. July 14, 2016. Available from Court Listener ↩