The Onion Router

The Onion Router (Tor) provides a means to access the Internet with potentially greater anonymity. It also permits access to hidden services, which form part of the dark web.

Video Lecture

History and Purpose

The Onion Router (Tor) was originally developed at the United States Naval Research Laboratory, after which it was spun off into its own 501(c)(3) nonprofit entity.1 Recent sponsors of Tor have included the State Department, Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), and the National Science Foundation (NSF).2 In the later discussion on this page about Tor and law enforcement, it is important to remember that Tor was created and is still sponsored by the United States government.

Tor’s objective is to provide anonymity while using the Internet. This system is designed in such a way that it is difficult to find the other endpoint of a Tor connection. If a user is connected to Tor, it is difficult to track their activities while using the network. From the point of view of a regular Internet server, it is difficult to locate a user who is connecting to that server via Tor. Consequently, Tor has a reputation for facilitating illegal activity, including the drug trade, child sexual abuse material (CSAM), stolen credentials and merchandise, and so forth. However, Tor also has numerous legitimate uses, including protecting both ordinary citizens and intelligence operatives working in repressive countries. Tor is freely available to anyone who would like to make use of it, although potential users need to be aware of some important security considerations.

How Tor Works

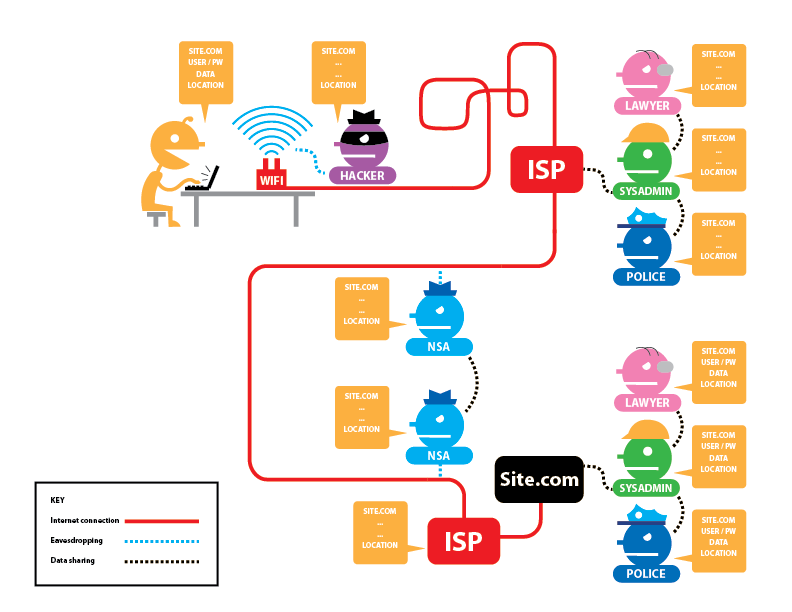

Normally, a regular connection to a website will use Secure Hypertext Transfer Protocol (HTTPS) as its means of encryption. As discussed in previous lessons, the Internet Service Provider (ISP) is able to monitor browsing activity due to a flaw in this encryption layer. However, as illustrated in Figure 1, there are actually two Internet service providers that can track users: the user’s own ISP, and the ISP to which the Web server is connected. There are also various other entities that can observe and monitor connections, including law enforcement and intelligence agencies (represented by the National Security Agency in the figure).

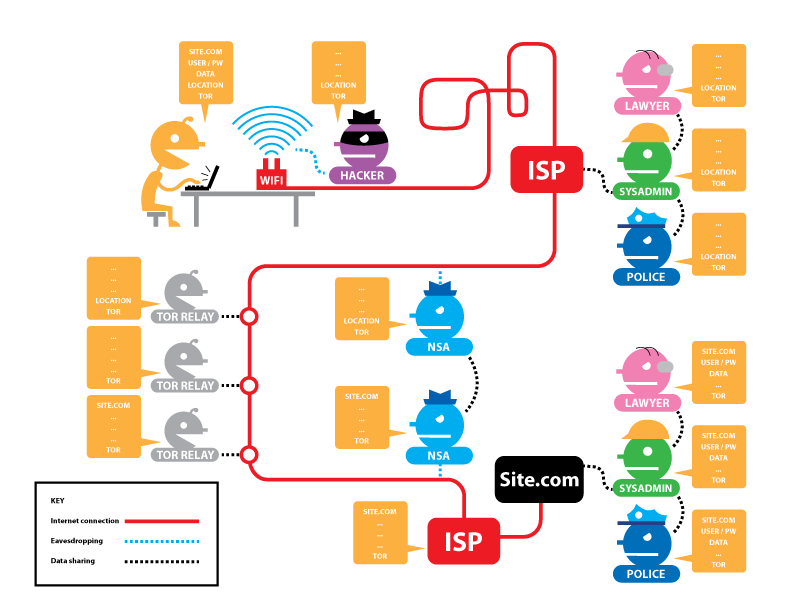

When Tor is in use (Figure 2), the connection to the Tor network is fully encrypted. An observer in the user’s local network or ISP knows the user’s location, and they can see that the user is connected to Tor. However, they cannot see which websites the user visits within Tor. At the other end of the connection, the Tor exit node (the third relay), any observers, and the destination website know the destination, but they see the source address as the address of the exit node. None of them are able to determine the user’s location.

The main reason that Tor obscures the user’s browsing activities is that it wraps connections in three layers of encryption at the user’s computer. When the connection reaches the first Tor relay, the relay removes one layer of encryption to determine the destination IP address of the second relay. At the second relay, one more layer of encryption is removed to locate the third relay. The third relay, which is also known as the exit node, removes the final layer of encryption and sends the original packets to the destination server. Since each layer peels away one layer of encryption to determine the next relay, this process is called onion routing (analogous to peeling layers from an onion).

Each relay only has the required keys to remove one layer of encryption, preventing any one relay from being able to spy on the encapsulated HTTPS connection. In addition, each relay knows only the address of the previous relay (or the sender) and the next address to which to send the message. No relay is able to reconstruct the entire connection path. Once a request reaches its final destination, the response is sent back using the same layered encryption technique.

In some cases, the final destination for a browser request over the Tor network might be to a server that is only accessible via Tor. A website that is only accessible from within Tor is called a hidden service and forms part of what is called the dark web. The dark web consists of websites that require special network tools – such as Tor – to access, and it contains a variety of content (only some of which is illegal, contrary to popular belief). Dark websites implemented as Tor hidden services use the .onion pseudo top level domain and have quite lengthy hostnames. For example, DuckDuckGo operates a Tor hidden service version of its search engine, and its address is the rather unwieldy duckduckgogg42xjoc72x3sjasowoarfbgcmvfimaftt6twagswzczad.onion.

Threats to Anonymity

Some federal agencies – the FBI in particular – are not fond of Tor, as it makes investigations significantly more difficult.4 This is a bit ironic, since Tor was originally conceived, and is still funded in part, by the federal government. As a consequence, we now have a situation in which one federal agency is trying to undo the work of others – a classic case of our tax dollars at work. There are several ways that the FBI, or perhaps some of the intelligence agencies (NSA, CIA, etc.), can try to unmask and de-anonymize a user.

One technique for de-anonymizing Tor users is to employ traffic analysis, which involves monitoring traffic flows at both endpoints of a connection and using some basic statistical calculations to confirm that a connection exists between those endpoints.5 As a practical matter, the Tor network is sufficiently large that it is difficult to identify both endpoints of a connection without somehow acquiring more information through a side channel. However, it is still theoretically possible for a global adversary to perform traffic analysis on the Tor network in real time if the adversary is capable of monitoring a sufficiently large portion of the global Internet. If any such adversary exists, it is most likely a nation-state-level intelligence agency.

Another way that a sufficiently well-funded entity could compromise the anonymity of Tor users would be for that entity to run a large enough number of relays that traffic would have a high probability of flowing through two or three of them. Since a single relay does not have enough information to remove all layers of encryption from a Tor packet on its own, multiple compromised relays would have to be configured to communicate on some type of side channel to track connections from end to end. This technique, which is known as a Sybil attack, has been observed on the Tor network and was potentially sponsored by a nation-state actor given the number of relays compromised.6

A significantly less expensive way to try to unmask users is for an adversary to run a malicious exit node in the Tor network. Since the exit node removes the last layer of encryption for each request made via Tor to websites on the public Internet, it is able to snoop on the original traffic created by the user’s browser. In the case of unencrypted connections, such as plain HTTP, the exit node can see the entire request and even alter it or send a phony response to it (called a man-in-the-middle attack). However, since the exit node can see the IP address of the destination server, and it can monitor HTTPS requests to observe the unencrypted Server Name Indication (SNI), the exit node can determine the destination of the traffic. If some piece of the observable, unencrypted part of the message reveals information about an individual, than that user can effectively be unmasked. Users can also de-anonymize themselves by logging into services like email or chat, voluntarily identifying themselves to websites.

Perhaps the most worrying method that the FBI uses to try to identify Tor users is euphemistically called a Network Investigative Technique (NIT). In reality, a NIT is simply a piece of government-sponsored malware that is delivered to a potential target. This malware may be specially crafted by former Tor developers with thorough knowledge of how the system works and what potential vulnerabilities are present.7 NITs are typically delivered by exploiting a flaw in the Tor Browser using JavaScript code, leading to a type of attack known as a drive-by download.8 The use of NITs is legally questionable, since the intentional delivery of malware is likely an illegal act in and of itself. To conceal this behavior, as well as to delay patching vulnerabilities in the Tor Browser that would render the NIT prematurely useless, the FBI closely guards details about these activities and will even move to dismiss cases involving heinous crimes in order to avoid having to disclose information about NITs in court.9

Civil liberties and the legality of intentionally using malware aside, a major concern that arises with the use of NITs is the potential for collateral damage to a bystander who suffers an unintended malware infection. The FBI is known to fund research into potential vulnerabilities that are useful for NIT development, while keeping those results secret and thereby preventing the vulnerabilities from being patched.10 There are also concerns about the amount of judicial oversight that is present in situations in which NITs will be deployed. In recent years, federal agencies have successfully managed to change Federal Rule of Criminal Procedure 41 to make it possible for any magistrate judge located anywhere in the country to issue a warrant to search and seize digital evidence located anywhere if the “district where the media or information is located has been concealed through technological means.”11 Government agencies can therefore “shop” around the country to find magistrates who are less technically inclined and thus might not understand the potential ramifications of the warrants they are signing. Such misunderstood warrants could be overly broad and result in delivery of malware to unintended targets.

In truth, the FBI really doesn’t need to deploy malware to catch criminals in the Tor network, as good old fashioned undercover police work can do the job quite well. One example of such an undercover investigation involves The Silk Road, which was a hidden service that facilitated transactions between buyers and sellers of various kinds of illicit goods and services (such as drugs, stolen credentials, stolen merchandise, and so forth). A multi-agency federal task force successfully infiltrated the service, took it down, and arrested its operator by planting an agent posing as a system administrator willing to help maintain The Silk Road. Ross Ulbricht, the operator of the service, was sentenced to life in prison since drug sales on the site led to overdose deaths.12 A less-publicized bit of fallout from the operation is that two of the federal agents who worked on the case – Carl M. Force IV of the Drug Enforcement Administration and Shaun W. Bridges of the United States Secret Service – also received prison sentences for stealing Bitcoin recovered as part of the seizure.13

Benefits and Risks of Using Tor

After reading the preceding material about some of the security risks inherent with using Tor, it might be apparent that using Tor to improve privacy potentially results in security trade-offs. While using Tor is one way to hide traffic from an Internet Service Provider, and it is also probably the best known way to achieve some degree of anonymity online, it is also a bit like the “wild west” of the Internet. Malware, illegal content, and markets for illicit goods are indeed present in a subset of Tor hidden services. Criminals may compromise parts of the system, particularly exit nodes, in an attempt to steal information, attack users, spread malware, or engage in other illegal acts. Similarly, the FBI and other government agencies may compromise parts of the system to steal (er, “investigate”) information, attack users, spread malware, or engage in other (probably) illegal acts. Tor users therefore have a higher probability of being exposed to more sophisticated attacks than a typical Internet or VPN user.

At the same time, Tor does have a few benefits when compared to VPN services in that Tor is available free of charge without a monthly or yearly subscription fee. All the software required to access the Tor network is open source and is readily available to anyone who wants to use it. However, a major downside to Tor relative to a VPN service, apart from the security threats, is that Tor relays are typically owned and operated by volunteers. Since a chain of 3 relays must be traversed in each direction to make a connection to a website, Tor has higher latency and is typically much slower than a VPN service. In many cases, Tor is not practical for consuming content that has a large data size, such as video.

Using Tor Safely

Using the Tor network safely requires first analyzing and mitigating the security threats to the extent possible. First and foremost, most malware designed to target Tor users (including FBI NITs) is designed for the Windows version of the Tor Browser. Therefore, under NO CIRCUMSTANCES WHATSOEVER should the Tor network ever be accessed from a Windows computer. The potential for the system to be compromised by a drive-by download is simply too great.

It might be tempting to believe that the Tor Browser on a Linux or macOS computer would be safer. However, although most malware might be designed for Windows, it isn’t impossible to find vulnerabilities in these versions of the Tor Browser. For this reason, using the Tor Browser on a regular Linux or Mac desktop is not advisable, since a drive-by download could still result in malware or illegal content finding its way onto the system.

The only relatively safe way to use Tor is via Tails, which is a live Linux distribution that runs from a USB stick.14 The computer is booted directly into Tails instead of into its regular operating system, and Tails is designed so that no traces of any activity are left behind on the computer’s internal disks. Even when using Tails, it is important to set the Tor Browser’s security level to the “safest” setting, which will disable JavaScript and thereby block the primary mechanism used by drive-by downloads. Obviously, booting into Tails and browsing the Web without JavaScript enabled isn’t a practical approach for day-to-day activities, so a VPN service is probably a better choice than Tor if the intent is simply to hide activities from an Internet Service Provider.

References and Further Reading

-

Image source: Electronic Frontier Foundation. “How HTTPS and Tor Work Together to Protect Your Anonymity and Privacy.” [License: CC-BY.] ↩↩

-

Dan Froomkin. “FBI Director Claims Tor and the ‘Dark Web’ Won’t Let Criminals Hide From His Agents.” The Intercept. September 10, 2015. ↩

-

Sambuddho Chakravarty, Marco V. Barbera, Georgios Portokalidis, Michalis Polychronakis, Angelos D. Keromytis. “On the Effectiveness of Traffic Analysis Against Anonymity Networks Using Flow Records”. Proceedings of the 15th International Conference on Passive and Active Measurement (PAM 2014), Los Angeles, CA, March 10-11, 2014. Available as a technical report from Columbia University ↩

-

Catalin Cimpanu. “A mysterious threat actor is running hundreds of malicious Tor relays.” The Record. December 3, 2021. ↩

-

Patrick Howell O’Neill. “Former Tor developer created malware for the FBI to hack Tor users.” The Daily Dot. April 27, 2016. ↩

-

Kevin Poulsen. “Visit the Wrong Website, and the FBI Could End Up in Your Computer.” Wired. August 5, 2014. ↩

-

Alexandra Burlacu. “FBI Drops Child Pornography Case To Avoid Disclosing Tor Vulnerability.” Tech Times. March 7, 2017. ↩

-

Eduard Kovacs. “University Responds to Accusations of FBI Funding for Tor Hack.” SecurityWeek. November 18, 2015. ↩

-

Cornell University Legal Information Institute. “Rule 41. Search and Seizure.” ↩

-

Sam Thielman. “Silk Road operator Ross Ulbricht sentenced to life in prison.” The Guardian. May 29, 2015. ↩

-

United States Department of Justice. “Former Secret Service Agent Sentenced in Scheme Related to Silk Road Investigation.” November 7, 2017. ↩