Internet Service Providers

Connecting a browser to a site on the World Wide Web requires crossing the Internet. Access to the Internet is provided by a company called an Internet Service Provider (ISP). Thanks to permissive regulations, ISPs in the United States are a privacy threat.

Video Lecture

The ISP Sees Everything

According to the Federal Trade Commission (FTC), Internet Service Providers (ISPs) frequently collect more information than necessary, target advertising to their customers using sensitive information, and offer real-time location information to third parties. Since the FTC has overlapping jurisdiction with the Federal Communications Commission (FCC), it isn’t always entirely clear which agency can take action against abusive ISP practices. The FTC ordered the six largest ISPs in the United States – AT&T, Verizon, Charter (doing business as Spectrum), Comcast (doing business as Xfinity), T-Mobile, and Google Fiber – to provide information about their data collection practices.1

Based on the FTC study, ISPs can (and routinely do) collect information from and about every device a subscriber uses with the service, including computers, mobile phones, smart TVs, and Internet of Things (IoT) devices including wearable devices, home appliances, thermostats, video cameras, and other connected equipment. Since many ISPs also offer other kinds of subscription services like cable television, telephone, or home security monitoring, they can collect data across product lines and merge the data into a comprehensive profile of the subscriber. In addition, ISPs can purchase information about subscribers from third-party data brokers and combine the purchased information with the collected information.1

Internet Service Providers have been found to use their subscriber data to target advertising at individual subscribers or groups of subscribers meeting specific criteria set by the advertiser. At least half the ISPs in the FTC study admitted to combining their subscribers’ personal information and browsing history to target these advertisements. Incredibly, the FTC also found that ISPs admitted to collecting sensitive data from individuals and targeting advertisements based on these data. Such targeting is a form of discrimination based on “race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, economic status, political affiliations, or religious beliefs.”1

The privacy policies of the ISPs in the FTC study have been found to be misleading and deceptive, intentionally hiding or using misleading language to avoid disclosing the various ways that subscribers’ data are used, sold, or transferred to other companies. Of the ISPs that provide the subscribers with any type of privacy controls, most of these privacy settings are just smoke and mirrors. The subscriber has few ways to opt out of having data collected and potentially retained indefinitely. With somewhat bizarre capitalization, the FTC staff have conclused that “Many ISPs in Our Study Can be At Least As Privacy-Intrusive as Large Advertising Platforms [sic].”1

The ISP Can Sell Everything

As if the unregulated and wholesale collection of subscriber data by Internet Service Providers were not bad enough, it is also the case that ISPs are legally permitted to sell any and all data they collect. This data collection and sale has been known to be an issue with mobile phone service providers for some time, as they have been able to sell real-time location data on subscribers to various third parties – such as bail bondsmen – with little government interference.2 In an effort to curb this type of sale, and to protect users’ browsing histories and other sensitive data from sale, the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) proposed regulatory rules that would have restricted this type of surveillance capitalism. However, a Republican majority in 2017 invoked the Congressional Review Act (CRA) in 2017 to block these rules from taking effect.3 President Donald Trump signed this CRA legislation into law on April 3, 2017, effectively giving ISPs the green light to continue unrestricted sale of subscribers’ browsing habits, real-time locations, and any other sensitive information.4

The situation outside the United States varies by country. In Canada, for example, ISPs are limited in what they can share without explicit user permission.5 Other countries with national privacy laws might have restrictions that protect subscribers’ data. However, some other countries may have repressive governments that require ISPs to collect and report subscriber activities to official agencies.

Records Retention

While the idea of laws mandating an Internet Service Provider to collect and retain information about its customers’ online activities might sound like the provenance of repressive dictatorships, some United States government agencies – particularly those involved in law enforcement – occasionally campaign for similar laws in the United States on the premise that retaining information could make it easier to catch criminals.6 Such mandatory retention regulations are opposed by privacy-oriented organizations like the Electronic Frontier Foundation. Government mandates for data retention are easily abused for the surveillance of ordinary citizens, creating the potential for government agencies to threaten free speech and stifle a free press by finding and suppressing information sources.7

Although mandatory retention laws have not yet been enacted in the United States, there are no prohibitions on indefinite voluntary data retention by ISPs. As a consequence, many ISPs have their own retention policies and will cooperate with law enforcement and other government requests. By way of example, Verizon Wireless reportedly maintains records showing which IP addresses have assigned to which subscribers for a period of one year. In addition, the company maintains records about all the websites a user visits while accessing the service for a period of one month.8 They and other mobile service providers maintain other types of records – such as logs of telephone calls – for much longer periods (years to decades) and will make them available to law enforcement with a subpoena, warrant, or sometimes even by request.9

Domain Name System

It might not be immediately obvious just how an Internet Service Provider can know which website a subscriber visits. While the provider can log information at the network level, showing the IP addresses to which a subscriber connects, this information doesn’t necessarily reveal browsing habits by itself, since multiple websites can be (and are routinely) hosted from a single IP address. To determine which websites a subscriber is visiting, the ISP needs another way to collect this information. One such way involves the Domain Name System (DNS).

Recall that DNS servers function as directories that map human-readable names (such as www.coastal.edu) to machine-routable Internet Protocol (IP) addresses (such as 199.120.21.79). Whenever a user desires to visit a website, the browser first makes a request to a DNS server to look up the website’s IP address. Once the browser knows which IP address hosts the website, it can make a connection to that address to access the site.

ISPs can figure out which websites a subscriber visits by providing their own DNS servers, which customer routers and computers will typically utilize by default. Since the ISP owns the DNS server, and the DNS server sees all the lookup requests coming from each individual subscriber, it is trivial for the ISP to log this information. By default, there is no encryption or other security involved when performing a DNS lookup on the customary User Datagram Protocol (UDP) port 53,10 so the ISP can implement this logging in the DNS server or by monitoring all the traffic flowing to the DNS server. One public example of known ISP DNS logging is that of Spectrum, which states in its privacy policies that DNS queries and associated device information are stored for 72 hours.11

It is possible for a subscriber to use an alternate DNS server, but configuring a router or other device to use a different server requires some technical skill. Furthermore, since the typical UDP packet used for a DNS query is not encrypted, it is easy for the Internet Service Provider to intercept packets destined for third-party DNS servers and redirect them to their own servers. This technique is called DNS hijacking and is within the technical capabilities of any ISP. An ISP has an economic motivation to direct users to its own DNS servers, since it permits the ISP to make money every time the user makes a typo when typing in the domain name of a website. Instead of returning a DNS error, an ISP can instead send the user to a page filled with targeted advertising.12

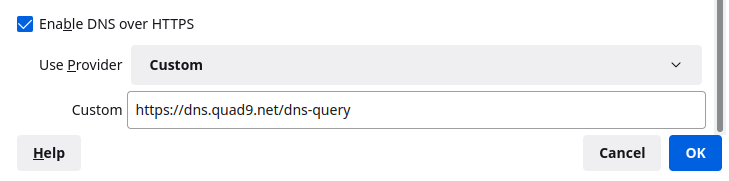

There are some ways to secure queries to the Domain Name System. Of the available methods, DNS over HTTPS (DoH) is the easiest to configure and provides encryption and certificate validation that prevent an ISP from logging or hijacking queries.13 As illustrated in Figure 1, Mozilla Firefox and derivatives provide a straightforward way to configure DoH. Some routers and other kinds of devices might also have DoH support.

Although DoH is a vast improvement over regular, unencrypted DNS queries, it is not a perfect solution. First, using a DoH service simply shifts the DNS query logging threat from the Internet Service Provider to the DNS over HTTPS provider. Second, unconditionally enabling DoH can cause connection difficulties on a campus network such as the one at Coastal Carolina University. On campus, internal DNS servers direct traffic differently from the off-campus servers. Some services might not work correctly (or be available at all) if an off-campus DNS server is used for lookups. Finally, securing the DNS server does nothing to stop the ISP from snooping on unencrypted website connections, and it also doesn’t plug the information leak present in the Secure Hypertext Transfer Protocol (HTTPS).

Limitations of Secure HTTP

While most modern websites now use Secure HTTP (HTTPS), there is a flaw in the encryption protocol that allows Internet Service Providers to determine which website a subscriber is visiting. Recall that an ISP can always see the IP address of any server to which the user connects, since the ISP is responsible for routing layer 3 packets from the user’s computer to that server. Since multiple websites could be hosted from a single IP address, this address alone doesn’t necessarily identify the website. If traffic were encrypted between the user’s browser and the website, it would appear that the ISP would not know for sure which website is being visited.

Unfortunately, the Transport Layer Security (TLS) standard that implements the “secure” part of HTTPS requires the browser to identify the destination website in cleartext (in other words, without encryption) before starting to encrypt the connection – this is called Server Name Indication (SNI).14 A fix for this information leak is under development, which will encrypt the SNI exchange. Originally called Encrypted Server Name Indication (ESNI),15 the latest version of this work is now called Encrypted Client Hello (ECH).16 When coupled with DNS over HTTPS, ECH should provide significantly more privacy from the ISP. At the time of this writing, however, this work is still just a draft and is therefore a long way from becoming widely available. Until it is finished and widely implemented, the ISP will continue to be able to monitor browsing activities easily.

Choosing an Internet Service Provider

Since the Internet Service Provider can see and sell all browsing activity, it is clearly necessary to choose an ISP carefully. By shopping around, it might be possible to find an ISP that doesn’t log user DNS queries and doesn’t snoop on user browsing activities. Careful selection of a provider, and careful review of privacy policies and service terms, will allow the typical consumer to select a company that doesn’t invade his or her privacy.

I’m just kidding, of course. In the United States, there is usually only one serious choice of ISP for any given address, since such providers typically have a local monopoly in a given area. There might only be one provider doing business within a single town or city, for example. Developers of neighborhoods might only contract with one provider to run the physical infrastructure (cable or fiber) within the subdivision. A condominium association or apartment complex might only contract with a single company, giving owners or tenants only one choice.

Even where multiple ISP choices are available, it isn’t uncommon for one provider to offer a much better quality of service than the other choices. For example, satellite Internet services might be available as alternatives to cable or fiber ISPs. However, satellite Internet will have higher latencies and lower performance than these wired alternatives due to signal travel distances and physical limitations of satellites. In places without unobstructed views of the sky or a convenient place to mount a satellite dish, there might be a choice between a much faster cable or fiber provider and a much slower and less reliable Digital Subscriber Line (DSL) option.

For those urban areas where there is actual competition between providers offering similar performance, there is no guarantee that any one company will be better than the others in terms of protecting user privacy. This phenomenon is already present with mobile Internet Service Providers, which are more commonly known as cell phone carriers. As part of its investigation into ISP privacy, the Federal Trade Commission also investigated all the major cell phone carriers, covering 98.8% of American mobile data customers, and found them all to be collecting information about subscribers and sharing that information with third parties.1 In many respects, mobile carriers are the worst possible choice for privacy, since they have access to the subscriber’s real-time location information and provide services to devices that are designed from the ground up to track the user and target advertisements. While non-cellular ISPs can also track the user’s location, this information isn’t nearly as valuable for invading someone’s privacy, since houses and apartment buildings tend to stay in one place.

References and Further Reading

-

Federal Trade Commission. “A Look at What ISPs Know About You: Examining the Privacy Practices of Six Major Internet Service Providers.” October 2021. ↩↩↩↩↩

-

Joseph Cox. “Hundreds of Bounty Hunters Had Access to AT&T, T-Mobile, and Sprint Customer Location Data for Years.” Motherboard. February 6, 2019. ↩

-

Chris Morran. “House Votes To Allow Internet Service Providers to Sell, Share Your Personal Information.” Consumer Reports. March 28, 2017. ↩

-

Harper Neidig. “Trump signs internet privacy repeal.” The Hill. April 3, 2017. ↩

-

Matthew Braga. “U.S. internet service providers get green light to sell user data – but what about Canada?.” CBC News. March 30, 2017. ↩

-

“FBI, politicos renew push for ISP data retention laws.” CNET. April 24, 2008. ↩

-

Electronic Frontier Foundation. “Mandatory Data Retention.” ↩

-

Verizon Wireless. “Law Enforcement Resource Team.” Presentation Slides. ↩

-

Patrick Siewert. “Cellular Provider Record Retention Periods.” Forensic Focus. April 18, 2017. ↩

-

Paul Mockapetris. “Domain Names - Implementation and Specification.” RFC 1035. November 1987. ↩

-

Spectrum Internet DNS Privacy Notice. August 20, 2020. ↩

-

Ryan Singel. “ISPs’ Error Page Ads Let Hackers Hijack Entire Web, Researcher Discloses.” Wired. April 19, 2008. ↩

-

Paul Hoffman and Patrick McManus. “DNS Queries over HTTPS (DoH).” RFC 8484. October 2018. ↩

-

Simon Blake-Wilson, Jan Mikkelsen, Magnus Nystrom, David Hopwood, and Tim Wright. “Transport Layer Security (TLS) Extensions.” RFC 3546. June 2003. ↩

-

Eric Rescorla, Kazuho Oku, Nick Sullivan, and Christopher A. Wood. “Encrypted Server Name Indication for TLS 1.3.” IETF Internet Draft. March 9, 2020. ↩

-

Eric Rescorla, Kazuho Oku, Nick Sullivan, and Christopher A. Wood. “TLS Encrypted Client Hello.” IETF Internet Draft. April 6, 2023. ↩